Helping Kids Cope with Political Stress

By Julie Weigel, LMFT

Family Therapist in Lafayette, CA

As an experienced therapist who has long supported divorcing families in Lafayette, CA, I’m noticing a growing sense of uncertainty in the homes of the general population—uncertainty that closely mirrors what I’ve seen in families going through divorce or separation. Children feeling distressed and desperate for a sense of control as they witness their parents’ reactions to the shifting sands of the current political climate and the resulting family dynamics, have begun to resemble children navigating parental divorce.

Having spent my career helping parents support their children through the instability of family transition, I feel compelled to share the tools and insights from that work to help all parents that grapple with how to navigate the current political tensions while upholding their values and addressing concerns about their children’s behavior, emotions, and education.

I have witnessed how we are all carrying a weight I haven't seen at this intensity before: a profound sense of hopelessness and powerlessness about the current political landscape. What strikes me most isn't that parents feel this way—it's that children are absorbing this hopelessness without fully understanding it. More than any political philosophy, kids seem to be picking up on something more fundamental and more frightening: the ambient despair of the adults around them.

When a child senses that the adults who are supposed to keep them safe feel powerless, it shakes their foundational sense of security. And unlike adults, who can at least name what they're anxious about, children often just feel the anxiety and misinterpret its source.

The Invisible Transmission of Parental Despair

In 25 years of practice, I've observed that children are extraordinarily attuned to their parents' emotional states. A parent doesn't need to spell it out "I feel hopeless about the government" for a child to absorb that hopelessness. It shows up in the parents’ tone of voice, in the heaviness that settles over dinner conversations, in increased time online, in the way a parent sighs while scrolling through news, or in the parental distractibility that can be felt in the car during the morning commute that drives the child into avoidance behaviors or attempts to seek reassurance by engaging parents in negative ways.

The irony is that many parents want to shield their children from political discussions and are working hard to do so, believing that silence equals protection. But children don't need explicit information to sense when their parents are frightened or despairing. In fact, the absence of explanation can make it worse—they know something is wrong, but they don't know what, which leaves them floating in free-floating anxiety.

As Jonathan Haidt documents in The Anxious Generation, we're already witnessing a crisis in adolescent mental health, with anxiety and depression surging as young people's lives have moved increasingly onto smartphones and social media. But there's another layer compounding this crisis: children are encountering what feels like collective adult despair while simultaneously having fewer real-world experiences that build resilience and problem-solving capacity.

Haidt argues that children need to be "antifragile"—they require some level of adversity and challenge (particularly through physical challenges and real life play, early in life to develop the capacity to handle difficult situations as adults. Without that experience, they become prone to anxiety, depression, and an inability to cope with stress. The combination of parental overprotection from real-world challenges and overexposure to under-regulated online material creates a particularly vulnerable generation.

When and How to Protect Them?

While I do believe that it is important to limit exposure to household news broadcasts that can be overheard (and seen) by children/teens, I also think it is important to consider the impact of shielding kids from knowing anything about current events. If the goal is to “protect them from my own fear and hopelessness," that's worth examining. Because your fear and hopelessness are already present—they're just unnamed. And unnamed anxiety is often more frightening than named reality.

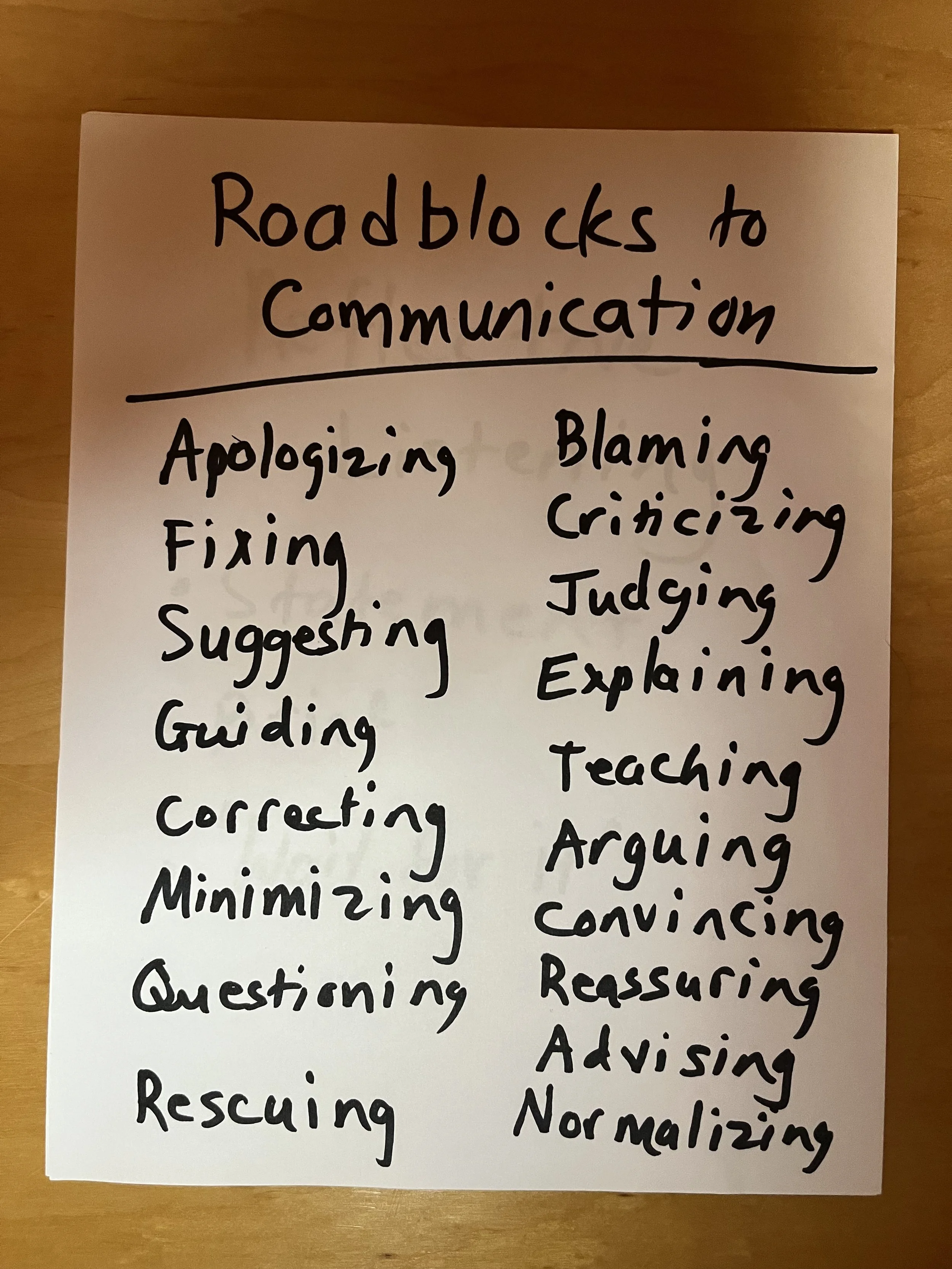

This doesn't mean you need to give your eight-year-old a detailed briefing on every political development. But it does mean considering how, and how much, to share your values and concerns in age-appropriate ways that don't transmit despair, I always teach parents to respond to children’s concerns and complaints with attuned listening before fixing, reassuring, or using other unhelpful “roadblocks to communication”. A general developmental guideline to consider, after spending some time simply attuning to the child’s complaint or need, is:

For younger children (ages 5-10): They need reassurance more than information. "Sometimes grown-ups disagree about how to make things better for everyone. Mom and Dad are working to help in the ways we can, and we're keeping our family safe." The message: There are challenges, and adults are handling them.

For tweens (ages 11-13): They can handle more complexity but still need it filtered through an empowerment lens. "There are some things happening in our country that I disagree with. I'm concerned about [specific value, like fairness or protecting the environment], and here's what our family does to live according to our values." The message: We have values, challenges to those values exist, and we take meaningful action.

For teens (ages 14+): They can engage with complexity and appreciate honesty. "I'm struggling with some of what's happening politically. I feel angry about [specific issue] and worried about [specific concern]. I'm figuring out how to stay engaged without becoming overwhelmed. What are you noticing about how this is affecting you?" The message: Adults struggle too, and we work through it.

The key across all ages: start with your child’s comments, concerns, complaints, and questions, providing them with attuned listening responses. When you have spent some time on this, it is ok to share your values and your constructive responses, but not your despair and paralysis.

How Much Information Is Too Much?

Parents wonder: Should I let my child watch the news? Should we discuss politics at dinner? How do I balance keeping them informed with protecting their mental health?

There's no universal answer, but here are guideposts:

Consider exposure, not just content. It's not just about whether your teen reads one article about climate policy—it's about whether they're spending hours doomscrolling through worst-case scenarios and catastrophic predictions. As Haidt documents, excessive and unregulated screen time contributes to social deprivation, sleep deprivation, and attention fragmentation. When that screen time is filled with distressing content, the impact intensifies.

Check your motivation. Are you sharing information because your child asked and is genuinely curious? Or are you processing your own anxiety by talking through it with your child? Children can be wonderful listeners, but they shouldn't be your therapist. One acronym I find both helpful and humorous is “WAIT (why am I talking?)” So often we are talking when anxious before checking our own emotional state (anxiety?) and the impulse (to reassure, teach, minimize, etc), in an unconscious attempt to avoid that feeling.

Notice the aftermath. Observe your child. If they appear more anxious, withdrawn, or catastrophic in their thinking after exposure to news or political discussions, that's feedback. Pull back. They may need less information and more connection and stability.

Model boundaries. If you're consuming news constantly, your child learns that staying immersed in distressing information is normal and necessary. If you set boundaries for yourself—checking news at specific times, turning off notifications, taking breaks—you teach them self control and self care, that it's possible to stay informed without being consumed.

The Cynicism Dilemma: When You Feel It Too

A common parental concern is along the lines of the following: "My teen has become so cynical about everything. They say nothing matters, that trying is pointless, that the world is broken beyond repair. And honestly? Part of me agrees with them. How do I foster hope in my child when I'm struggling to find it myself?"

This is the painful paradox of parenting during times of collective distress. You feel cynical about the state of things, and that cynicism feels justified, even rational. But you also desperately want your child to maintain some sense of possibility, some willingness to engage with life rather than retreat into nihilism.

Here's what I've learned: You don't counter your child's cynicism by pretending to feel hopeful when you don't. Children have finely tuned authenticity (BS) detectors, and false optimism will only deepen their cynicism. Instead, you model something more nuanced and more sustainable: the capacity to hold both legitimate criticism and ongoing engagement.

When your teen says: "Everything is corrupt. Why should I even bother caring about anything?"

The unhelpful response: "That's not true! There's so much good in the world!" (This dismisses their observation and feels patronizing.)

The equally unhelpful response: "You're right. Everything is terrible and there's no point." (This confirms their despair and models giving up.)

The attuned response: "You're seeing a lot that feels broken and unfair."

Pause. Stay with them in that statement (and know that it is temporary, part of a process of intrinsic problem solving). Then, after a few rounds of their complaints or ideas, only when they have had the opportunity to think it through aloud, in your loving and neutral supportive environment—not immediately, but after they've felt heard—you might add:

"I see those things too. And I still get up and do what I can. Not because I think I'll fix everything, but because sitting it out feels worse."

This models something essential: mature hope isn't naive optimism—it's clear-eyed engagement despite uncertainty.

You're not pretending the problems don't exist. You're demonstrating that awareness of problems doesn't require paralysis. You're showing them (not saying it, but showing it) that adults can hold complexity: "Yes, things are hard. Yes, I still participate. Yes, both can be true.” Be careful to model this without teaching or preaching.

Another common scenario: Your child expresses cynicism about their own future—"Why should I try in school when there won't even be jobs/a livable planet/a stable society by the time I graduate?"

Instead of: Debating the accuracy of their predictions or reassuring them everything will be fine.

Try: Notice your emotional response (worry? panic? fear? anger?) and your impulse (teach, contradict, suggest, question), and after getting clear on all that, use reflective listening, “You’re questioning whether effort even matters when the future feels so uncertain."

Wait. Let them sit with their own question. Allow them to think this through in a comment/reflection, then wait, followed by comment, then reflection, then wait cadence. At some point, it may be appropriate to add your perspective: "I don't know what the future holds either. Notice the impulse to weigh in and allow a little more space for your child to take the lead with ideas, whether they are “good” or “bad”. After restraining the impulse to respond, you may decided to say something like, “What I do know is that I've never regretted developing my capabilities, even when the path wasn't what I expected."

You're not promising them a specific outcome. You're modeling that growth and learning have inherent value, regardless of external circumstances. You're demonstrating agency—not control over outcomes, but ownership of your own development and choices.

The key is this: cynicism in young people is often a defense against the pain of caring about things that feel out of control. It's easier to declare nothing matters than to care deeply about something you feel powerless to affect. When you meet their cynicism with neither false optimism nor confirming despair, but instead with your own example of engaged uncertainty, you show them there's a third path.

You can acknowledge that the game feels rigged and still play your hand. You can see the brokenness and still create beauty. You can recognize what you cannot control and still act on what you can. This isn't toxic positivity—it's mature resilience.

The Art of Attuned Response: Moving Beyond Questions

When your child expresses anxiety, hopelessness, or overwhelm about the world, your instinct might be to ask questions: "What do you think would help?" or "How can I support you?" These feel collaborative, but they can inadvertently put pressure on a child who's already overwhelmed. Also consider that questions can be perceived as criticism.

Instead, I teach parents the power of attuned reflection—simply naming what you observe without rushing to fix or solve. This approach, which I explore in depth in my article on the power of silence in parenting, creates space for your child to access their own problem-solving capacity.

When your child says: "Everything is terrible and there's no point in trying anymore."

Instead of: "That's not true! Things aren't that bad."

Try: "You've given up hope."

Then wait. Stay present. Let them feel your steady, non-anxious presence. Your job isn't to talk them out of their feelings—it's to demonstrate that these feelings can be held rather than avoided.

When your child says: "I'm scared about what's happening in the world."

Instead of: "Don't worry, I'll keep you safe."

Try: "You're carrying a lot of fear right now."

Again, stay with them. Your calm, connected presence communicates something words cannot: "This feeling is manageable. Feelings are not dangerous. You can survive it. I'm here."

When your child says: "I don't know what to do about any of this."

Instead of: "Let me fix this for you."

Try: "You're feeling stuck and hopeless.” You might reflect their feeling wrong and get corrected. There’s nothing wrong with that. Just keep trying until you get it right. The caring and the intention are more important than being right.

The silence that follows is where transformation happens. In that space, your child begins to access their own resources, their own thoughts, their own capacity. Your presence provides safety; your restraint provides opportunity. It becomes a “vacuum of silence”, that draws out the intrinsic problem solving ideas.

This is the fine art of improvisation in parent-child conversations—staying present, attuned, and responsive without directing or solving. It requires practice and often, coaching. But it's one of the most powerful skills a parent can develop.

Building Problem-Solving from the Inside Out

As I discuss in my article on how parents' responses shape child emotional development, the way you respond to your child's distress literally shapes their developing brain's capacity for emotional regulation and problem-solving.

When you rush in to fix, soothe, or solve, you communicate: "You can't handle this." Or worse: “I can’t handle this”. When you stay present without rescuing, you communicate: "You have what you need inside you. I believe in your capacity. I trust you. You can trust you.” You say this without saying it. You SHOW it.

This doesn't mean turning away and abandoning your child to figure everything out alone. It means shifting from:

"Don't worry about that, let me handle it."

To: "This matters to you.”

Immediately offering solutions

To: "You're working on something important."

Taking over their problem

To: "You're figuring this out."

These aren't questions—they're reflections. They bounce the problem-solving back to your child while communicating your faith in their capacity. And over time, children internalize that faith and develop genuine confidence in their own abilities.

The concept of healthy boundaries, which I explore in my article on setting boundaries for parents and teens, extends to problem-solving too. Your boundary is: "I won't do for you what you can do for yourself." This isn't punishment—it's respect for your child's developing competence.

Staying Grounded When the World Feels Unsteady

Here's what I want parents to understand: Your emotional regulation is the most important gift you can give your child right now.

Not your political opinions. Not your ability to explain complex policy. Not your capacity to fix what's broken in the world. Your ability to stay grounded, connected, and present when everything feels uncertain. Your presence.

Developmental psychologist Mona Delahooke emphasizes that when parents have their own distress tolerance, they can "remain lovingly present and engaged through the wide range of their children's inevitable and expected negative emotions." This presence—not avoidance of discomfort, not rushed reassurance, not immediate problem-solving—is what helps children develop their own capacity to tolerate difficult feelings.

Your child doesn't need you to have all the answers. They need you to demonstrate that adults can hold complexity—can acknowledge real challenges while maintaining their center. When you doomscroll in front of them, catastrophize about the future, or become visibly dysregulated by news events, you're teaching them that the world is fundamentally unsafe and they are powerless within it.

But when you say, "I'm concerned about this, and I'm also taking care of myself and our family," you teach them something profound: it's possible to care deeply about things beyond your control without being destroyed by that reality.

Practical Steps You Can Take Today

1. Audit Your Emotional State

Before you can help your child navigate their anxiety, slow it down and spend some extended time noticing your own. Are you carrying hopelessness? Where do you feel it in your body? What would it look like to acknowledge your concerns while reconnecting with your own sense of agency?

2. Create Information Boundaries for Everyone

Designate specific times for news consumption—for you and your children. Turn off news notifications. Create tech-free zones where no one is scrolling through distressing content. The dinner table, family game time, and the hour before bed are sacred.

3. Practice Reflective Presence

The next time your child expresses anxiety, resist the urge to question, fix, or reassure. Simply reflect what you observe: "You're worried." "This feels big to you." "You're not sure what to do." Then wait. Stay present. Tolerate your own distress. Trust their process.

4. Normalize Uncertainty

"I don't know what will happen, and that's uncomfortable for me too." Acknowledging and modeling tolerance for uncertainty is one of the most valuable lessons you can offer.

6. Return to the Body and Real World

Physical play, outdoor time, and unstructured real-world experiences build resilience in ways that no amount of talking can replicate. Get outside. Move bodies. Create opportunities for your child to solve real problems—building something, fixing something, navigating something.

When to Seek Support

Sometimes despite your best efforts, you notice your child spiraling—increased anxiety, withdrawal, changes in sleep or appetite, talk of hopelessness that doesn't lift. Or perhaps you're finding it difficult to stay emotionally regulated yourself, and you recognize that your own distress is affecting your parenting.

These are signs that outside support might be helpful. Therapy isn't admission of failure—it's a tool for building the skills and capacity your family needs to navigate difficult times.

When parents ask me about finding a therapist, they often start with insurance questions. I understand—therapy is an investment, and practical concerns matter. But I also want you to consider what you're actually seeking. If your family is struggling with deep patterns, if you're trying to shift how everyone relates to anxiety and uncertainty, finding an independent therapist with experience and specialization matter significantly.

In my 25 years of practice working specifically with children, teens, and families, I've developed expertise in these exact dynamics—helping parents strengthen their own emotional regulation, teaching children to build distress tolerance and intrinsic problem-solving skills, and improving family communication during stressful times. That depth of experience allows me to recognize patterns quickly and guide families toward strategies that actually work. We can accomplish a lot in a single session.

Insurance panels are valuable, and I respect that they make therapy accessible. But I also want parents to know they have a choice. Sometimes the most effective path forward is working with someone whose entire practice is built around the specific challenges you're facing.

But does online therapy help?

Absolutely. Working with an online therapist can make it easier for kids and parents to get consistent, compassionate support—especially during stressful or uncertain times. Virtual sessions provide a safe space for children to express worries and learn healthy ways to manage anxiety and emotions. Many families find that online therapy can be just as effective as in-person sessions, allowing kids to feel comfortable in their own familiar environment while receiving the same quality of care. Whether you’re in Lafayette, Walnut Creek, or anywhere in California, online therapy offers flexible, effective support for families coping with political stress and everyday challenges.

The Long View: What We're Really Building

Will the political climate improve? Will your child's world become more stable? None of us can predict that.

But here's what I've learned in 25 years of working with families: The most resilient children aren't those who've been protected from all stress—they're the ones who've learned, with their parents' steady presence, that they can survive difficult feelings and solve problems from the inside out.

Your child will face challenges you cannot control. They will live through events you cannot prevent. But you can give them something far more valuable than a stress-free childhood: you can give them the internal resources—the distress tolerance, your supportive present and faith in the their ability to solve problems, the sense of agency—to navigate whatever comes.

That work requires intention, practice, and often guidance. If you're finding it difficult to stay grounded when your child is anxious, if you're unsure how much to share about your own concerns, if you want to learn the art of attuned response and improvised presence—this is work we can do together.

You don't have to navigate this alone. Sometimes the most resilient thing a parent can do is seek support in becoming the steady, regulated presence their child needs.

Ready to strengthen your family's resilience? Contact Julie for a free 30-minute consultation to discuss how therapy can support your family during uncertain times.

Related Articles:

She provides online therapy throughout California, with particular focus on building family resilience, strengthening parent-child communication, and helping both parents and children develop emotional regulation and problem-solving skills. Her approach integrates Internal Family Systems (IFS), drama therapy, and somatic techniques, with specialized training in helping families navigate anxiety and uncertainty.